Announcement

Collapse

No announcement yet.

โมให้ดีกันเยอะแล้ว มาม๊ะ....มาโมให้"เจ๊ง"กันดีกว่า

Collapse

X

-

> What's All This Current Limiter Stuff, Anyhow?

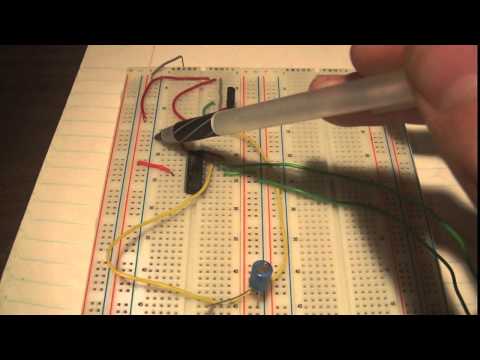

The other day I was studying a current limiter using a basic current regulator, which used an old LM317LZ (Figure 1).

Figure 1

I did the design on this IC about 20 years ago, with a little advice from Bob Dobkin. The LM317 was trying to force 40 mA into a white light-emitting diode (LED), so that 1.25 V across RS, the 30.1-ohms sense resistor, would cause a 41-mA current to flow? if you had enough voltage. (This is a GOOD standard application shown in every LM317 data sheet.) Because the output pin is 1.25 V above the adjust pin, the current I = 1.25 V/RS will flow? if there's enough voltage.

It worked fine with an input voltage of 9 V, or 8 V. But, of course, when it hit 7.4 V, it began dropping out of regulation. This was the basic design for a flashlight, using a white LED and a 9-V battery. The flashlight would run with RS = 30 ohms for a BRIGHT output, or 120 ohms for long battery life, and still provide enough light to hike with on a trail in the pitch dark.

I pondered this for a while. Would it do any better if I put the load in the + supply path of the LM317? How about installing the load between A and B, and placing a jumper wire between C and D? No, it would work just as well? and just as badly.

Then a few days later, I realized? I could do a lot better than that! Yes, an adjustable current source, such as an LM334N, might do a tiny bit better than an LM317. But see Figure 2.

Figure 2

The LM334N can regulate with not 1.25 V across the sense resistor? but just 64 mV. So a 1.6-ohms resistor will let you source 40 mA quite handily. And the voltage across the load does NOT have 0.7 V in series with it, so it regulates down MUCH better than Figure 1.

How much voltage is across the transistor? An ordinary 2N3906 will keep working down to 65 mV. So you can force 40 mA into a white LED that runs at 4.0 V, even down to a 4.13-V battery voltage. If you want to put 20 mA into a series stack of red LEDs, the conventional LM317 scheme will light two LEDs with a battery down to 6.3 V. But the LM334 scheme can drive three LEDs in series, with the same voltage. So it's not a bad circuit. This is a useful trick, especially if you have a load that's floating, and isn't grounded to either supply.

THIS circuit doesn't have a low tempco. Its output current increases at +0.33%/?C. But that's plenty good enough for many cases? like in a flashlight! If you need a better tempco than that, we know several ways to do it. Still, this will let you regulate the current into a red LED down to 2.1 V of supply voltage, or a white one down to 4.2 V? MUCH better than 7.4 V.

OH? I almost forgot to say? the LM334 sometimes needs a series RC damper. My first guess was 2 uF and 22 ohms across the base-emitter of the PNP. Actually, this circuit didn't oscillate or ring badly without an added capacitor, but the noise was a bit quieter when I added a 2 or 10 uF electrolytic.

If you really want a low tempco, use copper wire (magnet wire) for the resistor?that will cancel out nicely. You'll need 6 ft. of #34 gauge, or 10 ft. of #32.

Even if you did have a grounded load, this circuit would regulate down to 5.4 V?considerably better than 7.4 V.> What's All This Current Limiter Stuff, Anyhow?

The other day I was studying a current limiter using a basic current regulator, which used an old LM317LZ (Figure 1).

Figure 1

I did the design on this IC about 20 years ago, with a little advice from Bob Dobkin. The LM317 was trying to force 40 mA into a white light-emitting diode (LED), so that 1.25 V across RS, the 30.1-ohms sense resistor, would cause a 41-mA current to flow? if you had enough voltage. (This is a GOOD standard application shown in every LM317 data sheet.) Because the output pin is 1.25 V above the adjust pin, the current I = 1.25 V/RS will flow? if there's enough voltage.

It worked fine with an input voltage of 9 V, or 8 V. But, of course, when it hit 7.4 V, it began dropping out of regulation. This was the basic design for a flashlight, using a white LED and a 9-V battery. The flashlight would run with RS = 30 ohms for a BRIGHT output, or 120 ohms for long battery life, and still provide enough light to hike with on a trail in the pitch dark.

I pondered this for a while. Would it do any better if I put the load in the + supply path of the LM317? How about installing the load between A and B, and placing a jumper wire between C and D? No, it would work just as well? and just as badly.

Then a few days later, I realized? I could do a lot better than that! Yes, an adjustable current source, such as an LM334N, might do a tiny bit better than an LM317. But see Figure 2.

Figure 2

The LM334N can regulate with not 1.25 V across the sense resistor? but just 64 mV. So a 1.6-ohms resistor will let you source 40 mA quite handily. And the voltage across the load does NOT have 0.7 V in series with it, so it regulates down MUCH better than Figure 1.

How much voltage is across the transistor? An ordinary 2N3906 will keep working down to 65 mV. So you can force 40 mA into a white LED that runs at 4.0 V, even down to a 4.13-V battery voltage. If you want to put 20 mA into a series stack of red LEDs, the conventional LM317 scheme will light two LEDs with a battery down to 6.3 V. But the LM334 scheme can drive three LEDs in series, with the same voltage. So it's not a bad circuit. This is a useful trick, especially if you have a load that's floating, and isn't grounded to either supply.

THIS circuit doesn't have a low tempco. Its output current increases at +0.33%/?C. But that's plenty good enough for many cases? like in a flashlight! If you need a better tempco than that, we know several ways to do it. Still, this will let you regulate the current into a red LED down to 2.1 V of supply voltage, or a white one down to 4.2 V? MUCH better than 7.4 V.

OH? I almost forgot to say? the LM334 sometimes needs a series RC damper. My first guess was 2 uF and 22 ohms across the base-emitter of the PNP. Actually, this circuit didn't oscillate or ring badly without an added capacitor, but the noise was a bit quieter when I added a 2 or 10 uF electrolytic.

If you really want a low tempco, use copper wire (magnet wire) for the resistor?that will cancel out nicely. You'll need 6 ft. of #34 gauge, or 10 ft. of #32.

Even if you did have a grounded load, this circuit would regulate down to 5.4 V?considerably better than 7.4 V.Last edited by keang; 7 May 2014, 15:45:09.

Comment

-

> Current regulation for Heaters

Using a voltage regulator to maintain a constant voltage for the heaters is obvious. But using a voltage regulator as a current source to maintain a constant current flow into the heaters is less so.

One three pin adjustable voltage regulator and one resistor are all that is needed to make a current source, a high current one at that. The desired current is set by the value of the resistor, which is found by dividing the base voltage (1.25 volts usually) by the desired current. For example, if we want 900 mA, we use a 1.39 resistor, as 1.39 = 1.25 / 0.9 . This resistor will dissipate over one watt of heat in this example and must be rated for at least twice that value.

The advantage to the current source approach over the fix voltage one is that the current source intrinsically limits the current inrush to the cold heater to no more than its fixed current setting. This will greatly limit heater failures. A further advantage is that the current source based power supply is much less prone to odd output oscillations than the voltage regulator based one. I believe this is so because the output of the regulator does directly attach to a capacitor in the current source version, as the current setting resistor buffers it output. The falling feedback ratio with higher frequencies within the regulator creates an inductive quality in the regulator that can be provoked into oscillation with the capacitance presented by the output capacitor.

(The ninth 1989 issue of Electronic Design carried an excellent article by Errol Dietz, titled "Reduce Noise In Voltage Regulators." The author explained nicely why certain capacitor values provoked certain frequency oscillations and why an cheap electrolytic worked better than a expensive polypropylene capacitor at preventing oscillations.)

The limitation to the current source version is that it should be used only with single heaters or a series of heaters, but not a group of parallel heaters. If two 450 mA heater elements are used in parallel with a current source and one is removed, then the other will see twice the current it should.

Even if multiple current sources are needed in an amplifier, the simplicity of the current source version makes the current source version very attractive. And the relatively low current limitation of most IC voltage regulators also makes multiple current sources a safer approach.

-------------------------------

> Voltage Regulators with Series Resistors

Here is trick worth looking into: as fixed voltage regulators do not come in 6.3 and 12.6 volt varieties, use a regulator with a higher than needed output voltage and then using an output resistor to drop passively the output voltage to the desired value. For example, an 8 volt fixed regulator can feed one 6SN7 through a 2.8 ohm resistor, as (8 - 6.3) / 0.6 = 2.8.

True, this resistor will ruin the regulator output impedance, but this is of no concern when the load is a heater element. In fact, it will protect the heater at turn-on from too great a current inrush. In addition, it will buffer the regulator's output from the large valued capacitor that shunts the heater and thus prevent possible high frequency oscillations.

-------------------------------

> Directly Heated Filaments

Many of the previous heater tricks will not work with directly heated tubes like the 2A3 and 300B, as these do not have heaters: their cathode and filament are one. Consequently, connecting the filament to the wall voltage, for example, is the same as connecting the cathode to the wall voltage.

Like a heater element, however, the filament can be heated by DC or AC voltage. If AC voltage is used, the following technique can be used. The usual configuration for an AC powered directly heated tube is to use a center-tapped transformer with the outside leads connecting the filament and the center-tap connecting to ground either directly or via a cathode bias resistor. In the latter case, the cathode resistor is usually bypassed by a large valued electrolytic capacitor.

Bypassing this capacitor with a smaller valued high quality film or oil capacitor is both common and recommended. In spite of this effort to "speed" up the electrolytic capacitor, the signal must still travel through the filament transformer's secondary winding. The assumption being that this winding represents zero impedance to all frequencies. (I would like to see a test of various filament transformers to see what contribution they make to a directly heated tube's frequency response. If you have ever thought that you might get away with using a power transformer as an output transformer, you should test its frequency response first before going any further. The results will probably prove amazingly disappointing.

But what if instead of using just one small film bypass capacitor, we use two small bypass capacitors and connect them to the output side leads of the filament transformer? Now the transformer's secondary is bypassed as well. The highest frequencies will take the path provided

Comment

Comment